Vince Wade, March 29, 2015 – VinceWade.com

When Richard “White Boy Rick” Wershe, Jr. truly was a boy he and a pal used to ride their bikes through their east side Detroit neighborhood noting which houses were dope houses and who operated them. That knowledge would eventually lead Wershe to become a teenaged confidential—secret—informant for the FBI.

To understand how a kid could be an important FBI source it’s important to understand the Detroit of Rick Wershe Jr.’s world back then. The previous post provided a snapshot of the city’s mayor-monarch-emperor-dear leader of those days, Coleman A. Young and the culture of corruption among some in the police department. This post is about Detroit street life from the era when Rick Wershe Jr. was growing up.

Why, one might wonder, couldn’t the police see what little Ricky Wershe and his friend could see on their bike excursions through the neighborhood? Too often the police knew full well about the dope houses but allowed them to flourish. The dope houses kept operating because they were paying off the cops.

It’s time to say most Detroit police officers were and are hard-working and honest people doing a tough but interesting job in order to support their families and earn a decent pension. (Note to DPOA and LSA union members: don’t contact me to bust my chops about the term “decent pension.”)

But to use the description of Detroit’s illustrious former mayor, Coleman Young, some of the city’s criminals wore blue uniforms and silver badges.

The biggest Detroit police corruption case of Richard Wershe Jr.’s youth was the so-called 10th Precinct Case, also known as the Pingree Street Conspiracy. The 10th Precinct narcotics conspiracy indictment came down the year Coleman Young was elected mayor. There was police corruption before him. There was police corruption after him. Some things never change.

Before this case, the 10th Precinct was best known as the starting place of the 1967 Detroit riot. The riot began after a middle-of-the-night police raid on an illegal after-hours drinking and gambling joint known in Detroit as a blind pig. Black resentment of the mostly white police had been building. They were seen as an occupying force. Patrol units were backed up by precinct support cruisers known as The Big Foh (Four). Four burly, ready-to-rumble cops would cruise around in big black four-door sedans, each officer ready to bail out and kick ass if need be. They were armed with Thompson sub-machine guns and shotguns. On occasions, tracer rounds from the Tommy guns were fired in the air or at the ground ahead of a fleeing suspect to persuade him to stop. It worked.

One Big Foh officer had the nickname Rotation Slim. He wasn’t a particularly big guy but his street fighting skills were legendary. If he and his cruiser crew saw a group of black guys congregated on a corner and looking the least bit suspicious, Slim would jump out of the car and say, “I’m going to rotate around the block. If any of you are still here when I get back I’m going to beat the shit out of you.” The guys on the corner knew he meant it and knew he was quite capable of administering a severe thrashing. If you were black and male in Detroit, your civil rights any given day were whatever the Big Foh decided they were.

The police/community dynamic in the 10th Precinct didn’t change much after the riot. But the murder rate in the 10th was rising rapidly due to widespread dope dealing. There were growing citizen complaints that the drug trade was flourishing with the help of police corruption. A secret investigation was launched.

The investigation was a combined city/county task force effort led by George Bennett, a taciturn black lieutenant who deeply resented years of white racism in the Detroit Police department. Distrust of his fellow officers, especially the white ones, seemed to be Bennett’s default mind-set. There was a nagging suspicion Bennett’s superiors gave him the 10th Precinct investigation because they believed he would fail. They didn’t like Bennett’s complaints about racism in the department.

Bennett had a hand-picked team of investigators known as Detail 318 plucked from outside the ranks of the narcotics units. Most of Bennett’s investigators were black. To the surprise and perhaps dismay of many in the command ranks, Bennett and Detail 318 succeeded.

The “Pingree Street Conspiracy” was a massive prosecution. Each defendant was entitled to his own defense counsel who could challenge prospective jurors during the selection process. As a result, jury selection began in the large auditorium of the City/County building because there was no courtroom in the city large enough for the jury pool, defendants and defense counsel.

The defendants were narcs and major black drug dealers. It was a window in to the corrosive effect of illegal narcotics on the streets of Detroit. The list of defendants was long and included most of the members of the 10th Police Precinct narcotics unit led by Sgt. Rudy Davis. The accused officers were white and black. The color that mattered most was the color green, as in the cash that was lining their pockets. The beefy white sergeant and his crew were accused of taking bribes from some drug dealers in the precinct while ripping off their rivals in raids which amounted to plain police robbery. The civilian defendants included dope gangsters like Milton “Happy” Battle, George “Texas Slim” Dudley and Harold “Boo” Turner. Other characters in the case had names like Snitchin’ Bill and Alabama Red.

The 10th Precinct case was the result of a county grand jury indictment, which was based on the testimony of a number of witnesses who had been part of the scheme. They agreed to testify to get a deal on their own prosecution. That’s right. The 10th Precinct Conspiracy was a major case built mostly on the testimony of informants, of snitches.

This post will feature direct quotes from the prosecution’s court motion to bind the defendants over for trial. Quotes from the prosecution motion will be in italics.

The document provides a window in to drug dealing and police corruption in Detroit—two crimes Richard Wershe, Jr. helped the FBI pursue a few years later.

The prosecution alleged Milton “Happy” Battle was at the top of the competitive dope-slinging pyramid in the 10th Police Precinct. Eventually Battle pleaded guilty and he became a prosecution witness—a snitch—who was taken in to protective custody. His life was in danger for testifying against crooked cops.

When he was rockin’ and rollin’ in the 10th Precinct dope market, Battle understood the retailing concept of making his product available through easy-access:

These four witnesses have testified to at least 21 locations where Milton Battle sold heroin or cocaine.

A certain national coffee shop chain would have been envious of Battle’s market penetration in the 10th Precinct. Milton Battle showed a willingness to learn from the experience of other dope dealers:

Roy McNeal testified that Harold “Rook” Davis advised him and Battle that they could be free from raids on their narcotics house if they would pay off Sergeant Rudy Davis. Battle took this advice.

McNeal, Milton Battle’s drug business partner, was no slouch at the retailing game, either. Amid stiff competition to supply the junkies of the 10th Precinct, McNeal, also known as Alabama Red, blatantly advertised:

McNeal posted signs on telephone poles saying, “Buy one cap, get a free dinner,” signed Alabama Red. When the consumer purchased the narcotics he was treated to barbecue spare ribs, potato salad, pork and beans and white bread, with a Sunday special of turkey and dressing.

Alabama Red also grasped the concept of “full service”:

Besides selling narcotics, they would sell and rent needles and droppers to the users, provide “hit men” to find the veins of those addicts who could not do it by themselves, and were prepared to give emergency medical treatment in case of an overdose.

As for Sgt. Davis, the head of the Precinct Narcotics Unit:

The testimony against Rudy Davis reveals a pattern of increasing involvement in the narcotics trade. Davis started out by taking money to prevent police raids on dope houses but later progressed to setting up raids of dope pads and splitting the money and narcotics confiscated with his cohorts. These raids were done with Roy McNeal’s cooperation and were aimed at people who were competitors of McNeal’s and Battle. Thus Davis killed two birds with one stone: He eliminated competition for his favored narcotics dealers and at the same time reaped a handsome profit for himself in the form of confiscated money and narcotics.

Drug trafficking is a rough and deadly business, as the 10th Precinct case amply demonstrated:

Wiley Reed testified…that (James) Moody came around whenever Battle called him. Moody’s function was to kill people for Battle.

During the summer of 1970, Moody, under Battle’s orders, killed a narcotics dealer named Charles Birney at the LaPlayer’s Lounge. Battle ordered Birney’s death because he (Birney) owed Battle heroin and money.

LaPlayers Lounge, fittingly located on Joy Road in Detroit was a favorite hangout for dopers and hitmen. Once, a pair of hitmen came in looking for a man they had been hired to kill. They found him, with a bodyguard. They asked the bodyguard to step aside. He refused. One of the hitmen shrugged and said, “Take two.” They shot both men dead.

Homicide detectives relished taking witness statements at LaPlayers Lounge murders. One investigator told me there could be 10-15 witnesses to a murder yet when the police arrived, all of them claimed they were in the men’s room when the shooting occurred. The LaPlayers Lounge men’s room had enough space for a toilet stall, a urinal and a sink. That’s it:

Larry McNeal also testified to yet another murder by Battle in furtherance of his narcotics business. He testified that Battle told him that he had James Moody kill Burma Turner at La Player’s Lounge.

James Moody may have been Milton Battle’s go-to hitman but someone had to clean up the mess:

A continuing occurance (sic) in a narcotic (sic) conspiracy of this magnitude is the murder of people for reasons connected with narcotics. A corollary need to murder is the necessity of disposing of the body, a chore that Moe Bivens undertook for Battle.

The drug underworld is a dangerous place, even for hitmen like James Moody. He and a dope-house-robber named Wiley Reed once kidnapped Milton Battle until he paid some money he owed Moody. Wiley Reed was a tall dark-skinned black man notable for the large pinkish bandage he wore over one side of his face to cover the spot where his jaw had been, before it had been shot off.

One of Milton Battle’s pals in the dope trade was an older, tough-as-nails guy named George “Texas Slim” Dudley.

Roy McNeal testified in the summer of 1971, after the kidnapping of Milton Battle, he went to George Dudley’s house to pick up some cocaine from Battle. There was a cocaine-sniffing party underway, attended by Battle, Wiley Reed, Kenneth Reeves and James Moody:

An argument started between Dudley and Moody over the kidnapping of Battle from Dudley’s house on an earlier date. Dudley subsequently shot and killed Moody during this argument. Reed and Reeves stripped Moody’s body took it to the bathroom and Dudley ran water in the tub. Dudley then forced Battle to mutilate the body and Dudley then wrapped a bare extension cord around the body. They placed the body in the tub and plugged the cord in the wall. They wrapped the body in a blanket and tied it. Reeves brought Moody’s car to the rear of Dudley’s house and Moody’s body was placed in the trunk of his own car, a green and white El Dorado. Dudley, Reeves and Reed then drove Moody’s car to the Metropolitan Airport and McNeal, Reeves, Reed and Dudley returned to Detroit in Dudley’s car.

Dudley was driving a 1971 Cadillac Brougham, known in the ghetto as a Bro-Ham. It was cool to be seen cruising the ghetto in a new Cadillac customized with a diamond shape in the rear window while doing the “gangsta lean.” The driver would lean to his right and put his right arm on the armrest as opposed to sitting upright in the driver’s seat. For added style the driver might wear a so-called Big Apple hat which was cocked to the left so it would appear horizontal to the car while the driver leaned to the right. There was even a song about it.

Diamond in the back, sunroof top

Diggin’ the scene

With a gangsta lean

Gangsta whitewalls

TV antennas in the back

—Be Thankful for What You’ve Got – William DeVaughn

In addition to his cool car Dudley apparently had a large firearms collection which he put to good use:

Dudley’s involvement in the conspiracy went beyond selling narcotics and being the host for cocaine-snorting get-togethers and murders…Reed also testified that he has observed many bullet holes in a bedroom wall at 1410 Atkinson. This was the result of Dudley standing people up along the wall and shooting at them.

Murder among dopers was no big deal to the narcotics cops of the 10th Precinct:

Roy McNeal also made active plans to kill Reed. He told Patrolman (Robert) Mitchell that he was going to kill Reed for robbing his narcotics operation. Patrolman Mitchell told him, “If you kill the son-of-a-bitch, take him out to (sic) the house and if I take you downtown, there won’t be nothing done about it.”

Just like traffic cops who have a quota of tickets they must write each month, the narcs had raid stats to maintain. The prosecution’s bind-over motion noted an exchange between Roy “Alabama Red” McNeal and Patrolman Robert “Mustache” Mitchell. McNeal had been paying Mitchell but Mitchell’s assignment had changed, so he had an alternative idea:

“You know now I am with the Metro unit, and we have a lot of places we cannot get in. We need someone like you that can get us into these places.” McNeal agreed and was to receive half of everything confiscated on the raids he set up.

Narcs-on-the-take liked the idea of sharing seized dope with their criminal friends:

Wiley Reed testified that he was with Brenda Terry when Officers (Robert) Mitchell and (William) Stackhouse offered to give her a portion of the dope seized if she would set up dope houses for raids.

Sometimes things happened to disrupt the flow of police bribes. The corrupt narcs were forced to innovate. That’s how the idea of cops renting dope pads to pushers came to be:

Roy McNeal testified that in May of 1972 after the boundary lines of the 10th Precinct were changed and he was now living in the 13th Precinct, Patrolman Willie Peeples and Patrolman Charlie Brown contacted him on Pingree and Linwood regarding moving into the 10th Precinct. Officers Peeples and Brown, who were receiving and taking money from his dope pad at 1974-76 Pingree, told him they would rent him a place to use as a narcotics pad in the 10th Precinct.

One 10th Precinct narc, a black officer named Richard Herold, gave a whole new meaning to the term “honkey” according to the testimony of a woman who was running one of the precinct dope houses:

Alice Bailey James testified that she placed $100 on Officer Herold’s clipboard when he pulled up to her house and honked.

The damage to the community from the drug scourge was captured in the charges against defendant Guido Iaconelli, a civilian shop owner from Farmington Hills, a Detroit suburb. Iaconelli sold stolen goods. He ran a fencing operation:

Iaconelli told Roy McNeal to buy everything he could because it was hot and Iaconelli could sell it.

The reasons (sic) that this activity is so felonious is at least two-fold. With the disposition of this property made convenient and easy, the narcotics dealers were able to accept goods instead of cash, thus opening their habituating business to a whole new segment of the community.

Now those persons who did not have cash to support a habit but who could steal personal property from the community could also buy narcotics. Thus this barter system increased the volume of business for the narcotics trafficers (sic) while simultaneously increasing the number of victims—those who became addicted to narcotics.

The easy disposition of this stolen property also had a second major ramification. When narcotics dealers accept goods instead of cash this increases the attractiveness of burglary and larceny as a means of supporting a habit.

Most of the defendants in the 10th Precinct Conspiracy were convicted and served time. The prosecution was based almost entirely on informant testimony.

The old line that history repeats itself applies to police corruption, too.

In 1988, a few months after he had been sentenced to life in prison for selling drugs, Rick Wershe was back in the headlines for what he knew about police drug corruption. The city was rocked by the news that 125 police officers were under investigation by Detroit Police Internal Affairs for narcotics corruption and personal drug use.

Media reports said Wershe had told federal agents he had personally bribed a Narcotics Section sergeant, paying $10,000 to avoid raids on a specific address, but the sergeant wanted more money.

The story soon faded. Seemingly nothing happened.

In fact, Assistant Wayne County Prosecutor Patrick Foley visited Wershe in jail and made him an offer: help us prosecute the corrupt sergeant and in exchange we will offer you—nothing.

Wershe tells me he told Foley that the prosecutor’s office would have to give him immunity and some kind of reduction on his life sentence. Wershe says Foley, now deceased, became very angry and threw a fit. Wershe says he—Wershe—walked out of the meeting and back to his jail cell.

Is it possible White Boy Rick could have opened the door on a new police corruption case like the 10th Precinct Pingree Street Conspiracy? We’ll never know. The prosecutor at the time—a stuffed shirt named John O’Hair—wasn’t about to dilute his trophy prosecution and the accompanying life prison sentence imposed just a few months earlier on the media crime sensation known as White Boy Rick.

References:

Recommended Reading

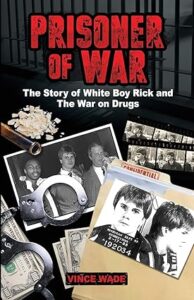

Prisoner of War: The Story of White Boy Rick and the War on Drugs by Vince Wade

What authoritative voices are saying aboutPrisoner of War: The Story of White Boy Rick and the War on Drugs:

“Meticulously researched and brutally honest. It tells the true story of White Boy Rick.”

—Ret. FBI Agent Herman Groman—Rick’s “handler” as an informant.

“With all of the ‘based on’ fluff and feathers coming out of Hollywood, Wade tells the true story of Richard Wershe, Jr., and how he landed behind bars for 30+ years. As usual, fact is more devastating that fiction.”

—Ralph Musilli, White Boy Rick Wershe’s longtime criminal appeals lawyer

The tale of a Detroit boy recruited by the FBI—at age 14—to be a paid informant against a politically-connected drug gang is so amazing it inspired a Hollywood film—White Boy Rick—starring Matthew McConaughey as the teen’s father.

What kind of father would take FBI cash to let his youngest child be an undercover operative in the murderous drug underworld? This book answers the question.

White Boy Rick became the Detroit FBI’s most productive drug informant of the ‘80s, but as the book explains, things went awry amid FBI misdeeds. Rick tried to become a cocaine wholesaler, got caught and has spent 30 years behind bars. He became a Prisoner of War: The War on Drugs. Rick Wershe is the central character in a wide-ranging exploration of the nearly half-century trillion-dollar policy failure known as the War on Drugs. It explains “testilying”, the widespread perjury felony committed by the police in pursuit of drug felonies, it examines CIA pressure to get charges dropped in a Detroit drug case and it shows how a basketball star’s drug death led to mass incarceration.

Order a copy of Prisoner of War and explore the appalling truth from the trenches of the War on Drugs.

Leave a Reply