In a self-published autobiography I’m sure you never heard of, a brash full-of-himself dope dealer from Detroit ended his 231-page love letter to himself by saying, “Hell. Somebody had to take over this city. Why not me?”

That’s an arrogant attitude, especially coming from a convicted dope slinger, but Y.B.I—Young Boys Incorporated, The Autobiography of Butch Jones tells us something about the mindset of Detroit’s criminal element when Richard J. Wershe Jr., aka White Boy Rick, was growing up on the city’s east side.

Wershe is a key figure in Informant America posts because, a) his life is more than a story; it’s an amazing saga and, b) his role as an FBI informant is a good tutorial on the dark, dark world of police informants.

In the previous post we noted in detail an infamous criminal case from the early 70s known as the 10th Precinct case or the Pingree Street Conspiracy. We recounted how Detroit heroin dealers conspired with corrupt cops to succeed and to dominate an ever more competitive market for the stuff of white powder dreams.

The lead defendant in that case was Sgt. Rudy Davis, the precinct narcotics crew chief in the Detroit Police Department’s 10th Precinct. Davis was convicted and sent to prison. But before that he and his crew were protecting dope dealers who were bribing them and as part of the deal Davis and his other corrupt narcs were robbing the dope houses of competitors. One of those competitors was Milton “Butch” Jones.

“…whenever I would see or even hear that Rudy Davis was ridin’ around the hood I would close down,” Jones wrote in his autobiography. “Because that was one guy that did intimidate me. Here was this guy that had the law behind him, a gun, and was also crazy as hell, so hell yeah that fool scared me.”

Jones complained in his book that Sgt. Davis and his crew robbed his dope houses several times. “Gettin’ rid of him was the best thang that the police department could have ever done,” Jones wrote. “Man did they do me a big favor.”

Young Boys Incorporated or YBI, the drug gang Jones helped create, had an innovative business strategy. He and his partners used boys under the age of 18 to handle retail street operations as much as possible. The police could not make a traditional narcotics case against juveniles. The Young Boys Incorporated gang was an innovator in the dope trade. The kids-peddling-dope innovation began in the 1970s so it wasn’t shocking in the early 80s when Richard Wershe, Jr. worked his way inside another major drug organization.

Jones and the YBI organization set new standards for boldness. They would frequently go to entertainment events as a group of 20 to 40. They were all dressed in the YBI “colors”—red and white. Red stood for blood and white stood for “China White”, the heroin they were selling.

Jones bought numerous Corvettes for his main players and bragged in his book about the time they drove as a group to the Cedar Point amusement park in northern Ohio.

“There were roughly eighty cars headed down the freeway,” Jones wrote. “…when we got to the freeway we was holdin’ the west side down baby!” Jones makes it clear they wanted people to notice. “Man we was flyin’ down the freeway with those flat-top John Dillenger (sic) (straw boater) hats on like we owned the mothaf**ka.”

Milton Jones also wrote about his drug gang’s disdain for the police.

“Man we took over the freeway that day. And check, the police wasn’t nowhere to found and if they was, they must’ve got specific orders not to mess with the Y.B.I.”

Federal indictments and convictions eventually put Young Boys Incorporated out of business. Milton Butch Jones is in prison serving a long sentence for operating a continuing criminal enterprise. But the problem of brazen drug dealing only got worse in the 80s, which were Rick Wershe’s teen years. It was the era when young Wershe was recruited to be a confidential informant for the FBI.

Crack cocaine engulfed the Motor City in the early 80s. The public outcry, the demand for action, was intense. It was worse, if possible, than the heroin epidemic that began in the aftermath of the 1967 riot.

When crack cocaine flooded the city, federal law enforcement was pressed in to action in the “War on Drugs” being waged on the streets of cities like Detroit. The FBI, DEA, Customs, Alcohol Tobacco & Firearms (ATF), IRS criminal investigators and the Immigration Investigations unit were tasked with doing “something” about the crack epidemic.

For the Federal Bureau of Investigation, combating narcotics was a big culture shock. Bureau agents had the smarts, they had the law enforcement tools, but most didn’t have experience with drug investigations.

A little background: I reported on the adventures of the Detroit FBI for many years. I got to know many of the agents well. I got to know more than most reporters about how the FBI works. Even the agency name has significance, in my view. It is the Federal BUREAU of INVESTIGATION. Part of the FBI culture is immersed in Bureaucracy. Part of the FBI culture is immersed in Investigation. Over time I came to view the FBI as an 80/20 organization.

I concluded 80% of the FBI’s agents did 20% of the work. Conversely, in my view, 20% of the agents did 80% of the work. The 80% were paper shufflers who went to great lengths to avoid making cases that might actually go to court. Retired FBI agent Gregg Schwarz, a hard-charger who admits he can be, um, outspoken, once launched in to a tirade in front of the Detroit SAC—Special Agent in Charge. Unlike other federal law enforcement agencies who refer to the boss as the “Sack” (SAC) the FBI prefers to pronounce each letter; S—A—C. They think it’s more elegant, I guess.

Back the Schwarz story. He was on the carpet in the SAC’s office, being admonished for some FBI rules transgression. He told the SAC that from that point forward he was going to become the perfect agent, one who never gets in trouble for trying to do the job in a dirty world of liars, hustling criminals and dope dealers.

Launching into a tirade, Schwarz said from that point forward he was going to do like many of his fellow Detroit FBI agents. He would show up for work on time, then go to out to breakfast with his squad on taxpayer time and gossip about other agents and Bureau politics. After a long, leisurely squad breakfast, Schwarz told the boss, he would come back to the FBI office, and join many other agents in changing in to workout clothes to go jogging on the taxpayers’ time and dime on Detroit’s Belle Isle, a recreation island in the middle of the Detroit River. Gotta stay in shape to fight crime, don’tcha know.

The big, long morning fitness run would be followed, Schwarz promised, by a nice long lunch, again on the taxpayers’ time, to be followed by hitting the streets to check out vague and mysterious “leads” that might, someday, if the stars aligned correctly, generate a real case. Before you know it, Schwarz told the SAC, it would be time to go home with no worries about getting censured for bureaucratic transgressions while doing real case work.

In my 80/20 example, 20% of the agents did 80% of the work. They were the real investigators, the get-it-done agents, the guys who didn’t watch the clock. The FBI 20-percenters included agents like Ned “Ned the Fed” Timmons, who told me he once had to explain to a stuffed shirt boss why he didn’t get a receipt for the bar tab when he bought drinks for some badass biker/dopers while he was working undercover on a major drug investigation.

Saturday night I was downtown

Working for the FBI

Sittin’ in a nest of bad men

Whiskey bottles piling high

(Opening lyric of Long Cool Woman—The Hollies)

Young Boys, Incorporated weren’t the only players on the dope scene that the FBI and other federal agencies were investigating.

The Chambers Brothers gang rivaled Young Boys Incorporated in terms of dope dealing success and the sheer scale of their operation. The Chambers gang also figures in the Rick Wershe story. They will be discussed in future posts.

Other gangs with hip names came and went, leaving plenty of dead bodies in the streets. The smart dealers endured longer. Demetrius Holloway is one example.

Scott Burnstein, author of the book The Detroit True Crime Chronicles wrote: ”Holloway was a business man’s gangster with a lethal reputation on the streets. He dressed like a corporate CEO, yet wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty either when the situation called for it. Smart, magnetic, feared and respected, Holloway embodied every quality of the consummate crime lord. It was a powerful mix that took him to astronomic heights.”

Using the corporation analogy, it’s fair to say Holloway’s Chief Operating Officer was Maserati Rick Carter. As the name suggests, Carter was flamboyant—until he was murdered. Violent disputes are common in the drug underworld and Carter became the victim of one such dispute.

Carter gave another dope dealer a shipment of cocaine on credit but a feud broke out when Carter tried to collect. There were several street shoot-outs until Carter finally got shot and was hospitalized for his wounds. While he was in the hospital, a hitman posing as a doctor went to Carter’s hospital room and finished him off.

Maserati Rick Carter went out the way he lived. He was buried in a coffin decorated to resemble a Mercedes Benz.

Holloway, too, was murdered by hitmen who shot him in the head while he shopped for socks at a men’s clothier located a block from Detroit Police Headquarters.

Another major drug organization lasted through most of the 80s by keeping a low profile. Johnny, Leo and Rudell Curry—the Curry Brothers—were not a brazen as Young Boys Incorporated and not as flashy as Maserati Rick, but they made plenty of money slinging dope.

The Curry organization was headed up by Johnny Curry, a savvy businessman who enjoyed a special relationship with the Detroit Police. Johnny was married to Cathy Volsan, the good-looking favorite niece of Detroit’s powerful mayor, Coleman Young. The mayor had an extensive personal security detail and part of their duties included protecting the mayor’s family. In the case of Cathy Volsan Curry, that meant keeping law enforcement trouble away from her door, even though she was married to one of the city’s biggest dope dealers.

The Curry organization was cruising along selling cocaine and raking in piles of cash. Then the FBI discovered that a white kid in the Curry’s neighborhood was friendly with them, and was trusted. That kid was Richard J. Wershe, Jr., later to be known as White Boy Rick.

For the FBI Rick was a gold mine of information about the Currys. There was just one problem. He was 14 years old. Recruiting a 14-year old to be an FBI confidential informant was dangerous business. The feds did it anyway.

Wershe went on to become a prolific FBI informant about Detroit’s drug underworld. Retired Detroit FBI agent John Anthony says Rick Wershe is arguably the most productive informant the FBI’s Detroit office has ever had in terms of convictions made with his help. Yet, Wershe remains in prison, denied parole for vague and mysterious reasons.

Future posts on Informant America will use law enforcement’s own documents and files to show the claim that Richard Wershe Jr. was a drug lord, a drug kingpin and a menace to society is totally false.

Recommended Reading

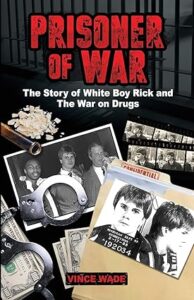

Prisoner of War: The Story of White Boy Rick and the War on Drugs by Vince Wade

What authoritative voices are saying aboutPrisoner of War: The Story of White Boy Rick and the War on Drugs:

“Meticulously researched and brutally honest. It tells the true story of White Boy Rick.”

—Ret. FBI Agent Herman Groman—Rick’s “handler” as an informant.

“With all of the ‘based on’ fluff and feathers coming out of Hollywood, Wade tells the true story of Richard Wershe, Jr., and how he landed behind bars for 30+ years. As usual, fact is more devastating that fiction.”

—Ralph Musilli, White Boy Rick Wershe’s longtime criminal appeals lawyer

The tale of a Detroit boy recruited by the FBI—at age 14—to be a paid informant against a politically-connected drug gang is so amazing it inspired a Hollywood film—White Boy Rick—starring Matthew McConaughey as the teen’s father.

What kind of father would take FBI cash to let his youngest child be an undercover operative in the murderous drug underworld? This book answers the question.

White Boy Rick became the Detroit FBI’s most productive drug informant of the ‘80s, but as the book explains, things went awry amid FBI misdeeds. Rick tried to become a cocaine wholesaler, got caught and has spent 30 years behind bars. He became a Prisoner of War: The War on Drugs. Rick Wershe is the central character in a wide-ranging exploration of the nearly half-century trillion-dollar policy failure known as the War on Drugs. It explains “testilying”, the widespread perjury felony committed by the police in pursuit of drug felonies, it examines CIA pressure to get charges dropped in a Detroit drug case and it shows how a basketball star’s drug death led to mass incarceration.

Order a copy of Prisoner of War and explore the appalling truth from the trenches of the War on Drugs.

Leave a Reply